Show Notes

In the spring of 1992, twenty-four-year-old Christopher McCandless left society behind, hitchhiking 3,000 miles into the Alaskan wilderness.

Two years earlier, Chris had donated his entire life savings to Oxfam, burned his social security card, and headed west seeking life on his own terms – without telling a soul, particularly his parents.

In this episode, we delve into Into the Wild‘s larger cultural implications, exploring the conflict between self and society, community and solitude. Philosophers like Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, and John Locke will weigh in. As well as George Carlin and Malcolm and the Middle.

We’ll investigate the concept of “wilderness” – how Euro-American settlers viewed it versus their Native American counterparts.

And for those of us who dream of escaping the troubles of society, we’ll explore McCandless as an inspiration and cautionary tale.

Citations

- Into the Wild [book] by Jon Krakauer (1996)

- Into the Wild [film] directed by Sean Penn (2007)

- George Carlin’s appearance on “Late Night with Conan O’Brien” (1996)

- “Malcolm in the Middle” [sitcom] (2000-2007)

- “How Chris McCandless Died” [article] by Jon Krakauer (2016)

- Myths of Wilderness in Contemporary Narrative [book] by Kylie Crane (2012)

Credits

Theme Music is “Celestial Soda Pop” (Amazon, iTunes, Spotify) by Ray Lynch, from the album: Deep Breakfast. Courtesy Ray Lynch Productions (C)(P) 1984/BMI. All rights reserved.

Transcript

I think you should really make a radical change in your lifestyle and begin to boldly do things which you may previously never have thought of them, or been too hesitant to attempt. So many people live within unhappy circumstances, and yet will not take the initiative to change their situation because they are conditioned to a life of security, conformity and conservatism, all of which may appear to give one peace of mind.

But in reality, nothing is more damaging to the adventurous spirit than a secure future. The joy of life comes from our encounters with new experiences and hence there's no greater joy than to have an endlessly changing horizon for each day. To have a new and different sun.

Days after writing that letter. Christopher McCandless. At the age of 24, went out on the road, stuck out his thumb, and hitchhiked 3000 miles all the way to Alaska.

He carried with him few belongings a 10 pound bag of rice, a field guide to the region's edible plants, a 22 caliber rifle, a camera, a dozen of his favorite books and ventured alone into a frozen landscape of windswept tundra, towering mountain peaks and endless stands of snow covered spruce.

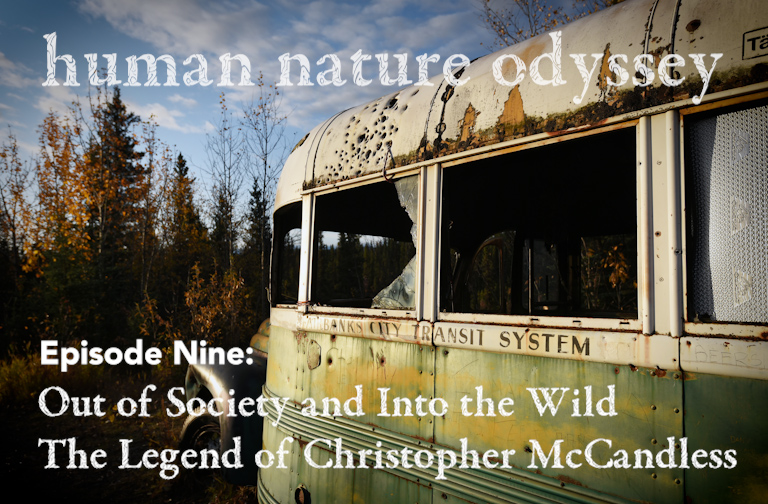

After a few days of hiking, Chris came to an abandoned bus. The bus had been emptied out and equipped with a cot, bed and stove. He carved a celebratory message onto a piece of plywood. His new found home. Two years he walks the earth. No phone, no phone, no pets, no cigarets. Ultimate freedom. An extremist. An esthetic voyager whose home is the road.

And now, after two rambling years comes the final and greatest adventure. The climactic battle to kill, the false being within and victorious conclude the spiritual pilgrimage. No longer to be poisoned by civilization, he flees and walks alone upon the land to become lost in the wild.

Welcome to Human Nature Odyssey, a podcast exploring what it's like to be stuck in a soul, stifling society, and whether it might be possible to escape. I'm Alex Lewis.

In the first season of Human Nature Odyssey, we traverse the ideas in Ishmael, a novel by Daniel Quinn. It was our deep dive into a telepathic gorilla's views on humanity, civilization, and the fate of the world. Ishmael believes that we're destroying the world not because we're evil or inherently flawed, but because we are captives of a self-destructive society.

I don't feel like a captive. Then how would you live if you wanted to? How would you drop out? Get a nice little farm and live off the grid somewhere? Well, you'd have to purchase a deed to the land. And to do that, you'd have to make money by participating in the economy somehow. Okay, fine. Scrap the farm.

You don't need to grow your food. You'll just live off the land as a hunter gatherer. Well, you'll find that most governments aren't too friendly with people trying to do that. When society starts to feel like one big cage, a sensible response might be to try and escape. That's what Christopher McCandless did. And that's why today we're following his footsteps, to see his path as both an inspiration and cautionary tale.

And if you stick around, I'll tell you what all this has to do with the 2008 sitcom Malcolm in the.

One night. Long ago, a DVD was rented at a blockbuster just outside Philadelphia by my parents. Left on the TV cabinet and found by a 15 year old me. It was the cover that got me. There was this young guy sitting up on the roof of what looked like an abandoned green bus, surrounded only by trees and a big empty sky.

What's that? Into the wild. My parents told me I might like it. So after dinner, I descended into the basement, slid the disc into the DVD player, and within a minute paused it. Realized this wasn't going to be just another movie, but an important sacred event. So I got off the couch, turned off all the lights, and sat cross-legged on the floor.

That was how I first encountered the legend of Christopher McCandless, who fled society, renamed himself Alexander Supertramp, and journeyed into the Alaskan wilderness. As I watched, I felt my life, what I expected from it. The limits that had been laid before me completely opened up. It felt like a light shining into a dark room, illuminating a whole world I didn't know existed.

Society sure felt like a cage to me then. I mean, what else was school if not one big cage were kept inside all day, rushed from room to room, given tests and quizzes, busywork, schoolwork, homework, all to prepare us for the prestigious collegiate level of tests and quizzes, busywork, schoolwork, homework. And then we'll find a job. If we're lucky, we'll be given a new place to stay inside all day and rather than grades, will receive a salary.

And we will work this job if we're lucky until we are old. And I. Up until that point, I truly didn't know it was possible to do anything else. But someone did. Someone like me. This was profoundly inspiring. I wanted to learn everything I could about Chris, but I'd never get to know him because in that very bus in Alaska, at the age of 24, Christopher McCandless died.

His body was found by a couple moose hunters just two weeks later.

Jon Krakauer, then a young writer for outside magazine based in Fairbanks, Alaska, was given the assignment to investigate this mysterious young man who died alone in an abandoned bus in the wilderness. All we're able to know about Chris's travels and demise is from what Krakauer was able to piece together in his investigation. He collected stories from people who spent time with Chris, the fragments of his journals, his notes in the margins of books he brought with him, and the letters he sent to the friends he made along the way.

It's the day of graduation from Emory University. Chris's parents couldn't be prouder. Chris had always given them a lot to be proud of. Growing up just outside Washington, D.C. in Annandale, Virginia. Chris had always been a star athlete and captain of the cross country team all throughout high school, and he had always been a brilliant student, so it was no surprise when he was invited to join Phi Beta Kappa.

What was surprising was when, for some reason, Chris declined joining the prestigious honor society. That never made sense to his parents. Chris, however, saw graduation completely differently. For four years, he had put up with the stuffy, meaningless exercise of following rules and paths that others laid out for him. And now Chris is free and no one can stop him from following his own path.

But this was a secret. His parents and younger sister made him to celebrate. They go out to lunch at a local restaurant in Atlanta. As Chris's dad greets him, he tells him, congratulations, son. This is a big step. From one perspective, this was a kind acknowledgment by a proud father. From another, it was a reminder that this is just one step on a long path.

Chris didn't want to go down. His parents tell him that as a graduation present, they're going to buy him a new car so he won't have to drive his old beat up Dotson anymore. To many, this would have been an awesome gift. But Chris wants nothing to do with it. I don't need a new car. I don't want a new car.

I don't want any things. These things. Things, things. His parents are concerned by this intense reaction. So the topic changes. They ask about his GPA and he tells them his grades are good enough for Harvard Law. This is true, but Chris has no intention of attending Harvard. Chris based his young adult life on his literary heroes Leo Tolstoy, Jack London, Henry David Thoreau.

It's Thoreau who wrote while living in a small cabin he built with his own hands the value of not just owning philosophy, but living it. To be a philosopher is not merely to have subtle thoughts, nor even to found a school, but so to love wisdom as to live according to its dictates. A life of simplicity, independence, magnanimity, and trust.

It is to solve some of the problems of life, not only theoretically, but practically unquote. Chris took this to heart. So without telling a soul, he donated $24,000 his entire life savings to Oxfam with the note feed someone with this. He burned his social security card and packed his few remaining possessions into his beat up old car and headed west, seeking life on his own terms.

He drove through the eastern forests, across open grasslands, and out into the red rock deserts of New Mexico. A flash flood wrecked his car, so he abandoned it triumphantly, burning the remaining cash in his wallet, and hitchhiked up and down the West coast to the placid waters of Lake Mead, the towering Sierra Nevadas, and the lush canopies of the redwoods.

When he needed money for supplies, despite now having a degree from Emory, he worked on a South Dakota combine, doing the most grueling work no one else wanted to do. When harvest ended, he worked at McDonald's. Even the money from these low paying jobs seemed too much for him. He wrote to a friend he met that my days were more fun when I was penniless.

Along with discarding wealth, renouncing authority, it was a moral obligation. So even after a railroad security officer caught him illegally riding freight trains and kicked his ass to dissuade him from doing it again, when the sheriff wasn't looking, Chris hopped right back on. He paddled a kayak down the Colorado River all the way to the Gulf of Mexico without a river license or any formal training.

He spent a few months living in slab City, an off the grid quasi anarchist commune in the southern California desert and on the outskirts of a small desert town. He found solitude near a nudist hot springs. He caught a ride with an elderly army veteran who soon became a close friend.

The old man so admired Chris's warmth. Discipline and integrity. He offered to adopt him as his grandson. Chris befriended hippies and outcasts wherever he went, but kept them at a distance, often leaving early in the morning before they woke without saying goodbye. Perhaps wary of being pulled back into the world, he was trying to escape.

And at some point in his travels out west, he started telling the friends he made along the way about his great Alaskan adventure. That was the plan. While working the South Dakota Combines, he sought advice on hunting and preparing his own game while living in the California desert. He started training his body physically and finally, when spring came, he made his way north to fulfill his ultimate dream of living off the land in the Alaskan wilderness.

Months later, when the news of Chris's death spread across the country. People had all sorts of judgments about him. He was woefully unprepared, cruel to his parents, just a privileged, wealthy kids seeking thrills. In a sense, Chris was on trial, which was ironic because for as much as society was judging Chris, he judged society right back. What is society?

It's not just the people around you, but the intangible things we generate when we're all together. The rules, the customs, the rituals, the taboos, the expectations. As comedian George Carlin once said, individually, I love them. Every person I meet. But when they start to group, when they get into clots, begin to surrender the beauty of the individual for the sake of the group as the group gets bigger.

Six, eight, 12, 15, 115,000 they begin to have hats, armbands, little slogans, lists of people they don't like and it gets out of hand. To be a human being is to navigate a contradictory relationship with the society we live in. Society provides us so much but also hinders us. It protects us, but also puts us in danger. It gives us identity and purpose, but only the ones it sets.

Society wraps its big arms around you. But it can be hard to tell whether it's in a loving hug or a stranglehold. This is where a classic philosophical work comes in. Say with me, Malcolm in the middle. What? What were you saying? Yeah, yeah. Malcolm in the middle. The indisputably greatest sitcom that started in 2000 and ran for seven seasons, featuring hilarious antics, heartwarming life lessons, and sophisticated yet subtle commentary on society.

In this one episode, teenage Malcolm works at the local Lucky Aid supermarket with his mom. One day, to his complete surprise. He finds a man hiding in a crack between two of the aisles. Turns out this guy has been living there for three years. You've been living in this store for three years? Are you crazy? Malcolm asks. The man responds, I don't know.

I just Malcolm. I had this super high pressure job. People were constantly hounding me for answers. Decisions, budgets, signatures. My nerves were a total wreck. I was wandering around here waiting for my Xanax refill my my cell phone and BlackBerry both going off, and I saw this crack and I decided to hide in there just for a few minutes.

And. It was fantastic. I didn't want to leave and then I didn't, and no one noticed. So I just stayed. Philosopher John Locke, who was a good philosopher, is no Malcolm in the middle, but good philosopher referred to our responsibility to society as the social contract. But it seems someone signed this contract for us without our permission. Long before we were ever born.

No one asked for our opinion. But like the guy living behind the cereal aisle, Christopher McCandless, believed the social contract could be voided. He did his best to tear it to pieces while gathering research for his book. Author Jon Krakauer tracked down the guy who gave Chris a ride to the trailhead. From where Chris began his hike. The guy told Krakauer that Chris said he didn't want to see a single person.

No airplanes. No sign of civilization. He wanted to prove to himself that he can make it on his own without anybody else's help, unquote. The American mythos is particularly admiring of this desire for independence. There's the story of people leaving their home to fend for themselves, whether it is immigrants in the New World or pioneers on the frontier.

Krakauer quotes Wallace Stegner on the American frontier, quote, it should not be denied that being footloose has always exhilarated us. It is associated in our minds with escape from history and oppression and law, and irksome obligations with absolute freedom. And the road has always led the West, unquote. Of course, the American frontier was already occupied, and the people living there were forced out so others could get away from their own society.

But as so many headed west to escape society, they brought society with them. And after just a century of settlement, American society existed from sea to shining sea. So Chris followed the allure of the frontier to one of its last remaining remnants, the Alaskan wilderness.

Where does one go to escape society? They go to the wilderness. As the naturalist John Muir once wrote, quote, thousands of tired nerves shaken over civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home. That wildness is necessity, useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life, unquote.

People seek the freedom that wilderness brings, land run by natural rhythms and simple necessities rather than artificial rules and arbitrary customs. The United States Wilderness Act of 1964, which designated over 800 federally designated wilderness areas, stated that, quote, a wilderness in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain unquote, according to the Wilderness Act.

And much of our culture's perception of nature, a true wilderness must have no people in it. But I don't know. Maybe this kind of thinking just reinforces the bars of our cage, rather than freeing us from it by asserting that wilderness is where people do not belong. We assert our separation from it. But this overlooks the fact that not all societies view society and wilderness as so opposed to each other.

Author Luther's Standing Bear, the Oglala Lakota, pointed out in the early 20th century, quote, we did not think of the great open plains, the beautiful rolling hills and winding streams with tangled growth as, quote unquote, wild. To us, it was tame. Earth was Bountiful, and we were surrounded with the blessings of the great mystery. Only to the white man was nature a quote unquote wilderness, unquote.

But for those of us living in a society separated from nature, always trying to restrict and control, exploit and manage its wild, it can make sense to assume that humanity's inherent role in nature is as a foe. And Chris didn't want to restrict or control nature any more than he wanted to be restricted or controlled himself. Chris's old friend from high school told Jon Krakauer that Chris quote was born into the wrong century.

He was looking for more adventure and freedom than today's society gives people, unquote. In the 1998 Jim Carrey film The Truman Show, a young Truman stands up in front of his class and proudly declares, I like to be an explorer, like the Great Magellan. His elderly teacher dutifully informs him, oh, you're too late. There's really nothing left to explore.

More than ever before, we live in a world that has been fully mapped out. In fact, there's probably a map of the whole world in your pocket right now. Pick any spot on the entire globe and you can see the topography, terrain, satellite view, street view, and detailed directions on exactly how to get there and where we can't go directly.

We can still examine in great detail. We can see the bird's eye view of remote Pacific islands. We can inspect the snow covered peaks of Antarctica. We can hover over the moons of Jupiter. Maybe that's why so many people increasingly think we're living in a simulation. After all, we're spending our lives looking more at these simulations than we are at the actual world.

But as the saying goes, these maps are not the territory. Just because the world has been mapped out, does that mean it's actually truly known? What have you discovered for yourself? What have you seen with your own eyes? What have you felt with your own hands? Traveled to with your own feet? How much direct contact with life do we really have?

Chris wanted direct contact, but even the supposed Alaskan wilderness Chris ventured into was only 20 miles or so from town, and had been fully mapped out. So Chris had a creative solution. He just wouldn't bring a map for Chris. It wouldn't have been a real test without having to survive entirely on his own. Now, many don't have to leave society to experience this.

For them, living in society is struggling to survive in and of itself. But born to a wealthy family with all the privileges he had. Survival was something Chris could only truly experience outside of a society designed for his protection. I could imagine someone arguing that sacrificing your comfort to experience survival is foolish. Almost disrespectful, to the people who have no choice but to just survive.

But I don't know. I can see the value in someone from affluence renouncing their status to experience struggles. Others are forced to. Of course, the risk of hitchhiking across the country, going into remote rural areas alone would have been even greater had Chris's race or gender been different. The fault, however, does not lie with Chris, but with a society that determines the conditions of our confinement based on our social status.

Because for Chris, this wasn't just idealism or romanticizing other lifestyles, it required real physical risk. But he wasn't just a daredevil. His risks were taken to serve philosophical pursuits and live life on his own terms.

But while Chris was having the adventure of a lifetime, his parents lives were falling. The pieces. For almost two years now, they had no idea where he was. When I first watched the film as a teenager, that seemed like a sad side note, but ultimately I felt Chris did what he had to do. Revisiting the story even just a few years later, Chris's total rejection of his parents started to feel a lot more cruel.

For most of us, the parent and child dynamic is a microcosm of the society and individual, echoing our contradictory relationship to society. Our parents bring us into this world are our reason for existing. They protect us from harm, teach us what they know, yet they confine us. They limit us. They give us baggage we struggle to unload for the rest of our lives.

It's a precarious relationship to be so reliant on these people, so under their control. Another high school friend of Chris's told Krakauer, quote, I think he would have been unhappy with any parents. He had trouble with the whole idea of parents, unquote. As a kid, I felt like the authority of my parents was a form of tyranny. I mean, our house was not a democracy.

We were given orders. We were given punishments. And if we behaved, we were given an allowance. But we were also given love, support, protection, guidance. Yet in my more rebellious moments, even these seemed restrictive. As Krakauer put it, quote, children can be harsh judges when it comes to their parents disinclined to grant clemency. And this was especially true in Chris's case.

Uncle. We can't be sure which evidence in particular Chris would have brought to parent child court. Perhaps it was their judgments about his lifestyle and conflicts over the value of materialism and traditional careers. Maybe it would have been his father's rage filled episodes. Or, Krakauer speculates, it could have been the discovery that his parents had lied to him and his sister about having them out of wedlock, or his father had a whole other family.

A secret Chris learned in college but never got on. Perhaps he would have presented all this as damning evidence. Either way, his judgment was clear. He cut off all communication with them, left no goodbye note, and never talked to them ever again. This severe sentence, as you can imagine, left Chris's parents devastated. Absolutely shattered. They went to bed every night, heartbroken, with no idea where he was.

Years later, Chris's dad wondered to Krakauer quote, how is it that a kid with so much compassion could cause his parents so much pain, unquote? I can almost hear Chris indignantly retort, right back at you, dad. But for Chris, he clearly believed he could only achieve his mission of self-discovery and independence by breaking away completely. Had he told his parents of his plans, they probably would have done everything they could to dissuade him and stop him.

So Chris skipped all that. He just left.

In Alaska. Chris wrote Thoughts and reflections in the margins of the books he brought. It's from these we catch a glimpse into how he spent his time. And we know that after 67 days in the wilderness hunting, foraging, and successfully living off the land, he had decided the time had come to return to society. On a strip of birch bark, he made a checklist of all he had to do patch jeans, take potatoes, organize, pack, shave.

But upon leaving he found the shallow river he initially forded. On the way in was running so high it was now impassable. He decided the best thing to do was return to the bus and wait for the river's seasonal water level to lower until it was passable. This was when his fate changed. He had passed his test of living off the land for two months.

Now he'd find out how much longer he could make it. Day 100 made it Chris Martin's journal. But in weakest condition of life. Death looms as a serious threat. Too weak to walk out. Have literally become trapped in the wild. Chris barely had the strength to move. What alone hunt and forage on the scale he needed to survive?

Days passed and evidently things got worse. We can only imagine the turmoil Chris went through as he came to grips with the severity of the situation, as he weakly got the strength to go off and forage for berries, he left the note behind that should anybody come to the bus while he was away, that he was in desperate need of help.

But help did not come, and Chris's body continued to shut down. He had conducted his spiritual pilgrimage in the Alaskan wilderness for 112 days. Two weeks later, his body was found by a couple of hunters. They reported it to the police, who recovered his remains. Among Chris's few belongings was a roll of undeveloped film he'd taken while in Alaska.

Once developed, one of the photos revealed a very skinny Chris taking a self time photograph outside of the bus for as terrified as he must have been. It seems there was also an ultimate acceptance, even peace, in the photograph. He held a final note that read I've had a happier life and thank the Lord. Goodbye and may God bless all.

When news of McCandless death made its way from Alaska to the rest of the country, many were not impressed. Some were vitriolic. Krakauer shares the not so pleased mail he received after writing the outside article. One wrote to him, quote, personally, I see nothing positive at all about Chris McCandless. His lifestyle or wilderness doctrine. Entering the wilderness purposefully ill prepared and surviving a near-death experience does not make you a better human.

It makes you damn lucky, unquote. Alaskans seem to be the most upset of all. One local wrote, quote, over the past 15 years, I've run into several McCandless types out in the country. Same story. Idealistic, energetic young guys who overestimate themselves, underestimated the country and ended up in trouble. McCandless was hardly unique. There's quite a few of these guys hanging around the state, so much alike that they're almost a collective cliché.

The only difference is that McCandless ended up dead with the story of his dumb ass sadness splashed across the media, unquote. But as Krakauer put it, quote, it is hardly unusual for a young man to be drawn to a pursuit considered reckless by his elders. Engaging in risky behavior is a rite of passage in our culture, no less than the most others.

Danger has always held a certain allure. That, in large part, is why so many teenagers drive too fast and drink too much and take too many drugs. Why? It has always been so easy for nations to recruit young men to go to war. It can be argued that youthful derring do is in fact evolutionarily adaptive and behavior encoded in our genes.

McCandless, in his fashion, merely took risk taking to its logical extremes, unquote. We can criticize him for the challenges he took on, but ultimately, the level of risk Chris took was his own choice. As we get older, we tend to look back and call these risks foolish. They are dangerous, but I'm not sure they're foolish. On a certain level, the young know what they're doing.

It's not that they are doing it because they didn't know it was dangerous, but precisely because it's dangerous. The young are testing the universe. It's the same when a toddler knocks over a glass vase. Even when they're told not to, kids misbehave because they're essentially testing. What are you going to do about it? That's how we learn. There are consequences for our actions, and we learn to accept or to challenge them with a healthy balance of rebellion and respect.

To give insight into Chris's quest. Krakauer shares that he himself, as a young man, went on a bold and very risky solo expedition up a mountain in Alaska called Devil's Thumb. Krakauer writes about how he was up thousands of feet in the mountain, caught in a snowstorm. The plane he hired to drop off supplies couldn't deliver them, and the young Krakauer accidentally burnt a hole in his tent from smoking a joint.

He admits the difference between himself and McCandless is complete luck. The fact that I survived my Alaska adventure and McCandless did not survive his was largely a matter of chance, unquote. If anything happened differently, Chris could have returned and he could have become the author reflecting on his adventures. But he didn't. And that's what's heartbreaking. Of course, Chris's death brought the most heartache to his parents, who were already shattered by his estrangement.

Krakauer spent a lot of time with Chris's parents while researching and writing the book. They eventually even considered him family. Describing Chris's mom's grief, Krakauer wrote, quote, she breaks down from time to time, betraying a sense of loss so huge and irreparable that the mind barks at taking its measure. Such bereavement, witnessed at close range, makes even the most eloquent apologia for high risk activities ring fatuous, and how unquote Chris claimed to never want to speak to his parents again.

But a few things betray his love for them. When the authorities found Chris's abandoned car near Lake Mead, they found a guitar in the backseat. The same guitar Chris's dad bought his mom. When Chris was born. The same guitar. Chris's mom used to sing lullabies for him as a baby. And when hikers discovered Chris's body in the bus in Alaska, it was wrapped in the sleeping bag that his mom sewed for him.

This is the guy who earned his money detested possessions. But Chris kept these items from his parents on his adventures. He even trekked into Alaska. Life is too short not to forgive what you can and learn to love from the right amount of healthy space. But Chris didn't get the opportunity to have that healing with his parents. Perhaps that's the greatest tragedy of all.

Why exactly Chris died was a mystery. After all, he had hunted and gathered his own food for months without a problem. What changed? Crack hour's investigation for outside magazine led him to believe that Chris confused the wild, sweet pea plant for the wild potato, too closely related species that look almost identical. But with one major difference the wild potato is edible, but the sweet pea is poisonous.

This fatal error could be seen as a case in point for Chris's foolishness and arrogance. But Krakauer pointed out, even expert botanists and indigenous people from this region have made this mistake. But a few years after the book's release, Krakauer was not satisfied with his assessment of Chris's death and conducted further research with other mean analytical services in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

These new findings indicate that Chris's decline actually had been from the potato seeds he gathered. They were correctly identified and edible, but had become moldy, which is what made him too weak to continue to do the things needed to survive.

It's really hard to exist when you're living off the land, especially when you're doing so well. For someone who loved Ishmael as much as I did, who saw the flaws in our society and wanted to imagine living a different way, Chris’s story was a natural inspiration. Apparently I wasn't alone in this. Daniel Quinn, the author of Ishmael, noted the impact into the wild seemed to have on many of his readers.

On his website, Ishmael.org, which is still up and running, he wrote, quote, I hear from so many youngsters who, like Chris McCandless, dream of fleeing civilization, of striking out on their own in the wilderness, of living off the land, unquote. But then Quinn went on to caution, quote, humans did not evolve as rugged individualists. Each taking on the task of survival on his or her own.

Our ancestors always faced the task tribally and never took it on single handedly. They knew that even with all their survival wisdom garnered over countless generations living in the wild is far too much for any isolated individual to cope with, unquote. Just as we as a species can't live without nature, we as an individual can't live without community.

But our society, our global industrial civilization, is not all societies. Just because our society is so restrictive and repressive, that doesn't mean community inherently has to be so. Chris learned this even on his travels. He couldn't help but make friends along the way and be part of, even temporarily, small communities that supported each other. When Krakauer recovered the things Chris left behind in the bus, he found the passage of the book Doctor Zhivago, underlined by Chris's hand that read, quote, happiness only real when shared, unquote.

Krakauer wondered if this showed he had, quote, changed in some significant way. He was ready, perhaps, to shed a little of the armor he wore around his heart. Stop running so hard from intimacy and become a member of the human community, unquote. If we're going to escape from our societal captivity, we're going to have to do it together.

Which brings us back to Malcolm in the middle.

So Malcolm finds a guy living behind the cereal aisle and has to decide what to do. While Malcolm is sympathetic of this guy trying to escape the pressures of society, Malcolm's mom, Lois, is not as supportive. When she finds the trespasser, she declares righteously in her classic no nonsense Lois way. Attention and lucky a trespasser. You do not get to do this.

You do not get to live off the grid. If anyone on the planet was entitled to hide from all the aggravation, it would be me, but I don't. Do you understand? No one gets to shirk their share of the misery. Everyone has to be stuck in this together. That's what's fair. Those are the rules for Lois. And perhaps for some who learn about Christopher McCandless story.

The real crime is that he tried to leave what the rest of us are trapped in. When I first watched Into the Wild at 15, I admired Chris's extreme idealism. I love the purity of what Chris did. I saw so many adults fall far short from the ideals they espoused at the time. Any compromise to my own ideals seemed cowardly.

And I still think there's value in that conviction. As we get older, we may become too cautious, too unwilling to take chances, to stand up for what we believe to be right, even when it's hard. But something I've come to value as I've gotten older is to see one. The need for balance in the life, and two. The impurity of life.

To not get religious about what's pure and what's sinful, but to see God in all of it. To not be so rigid and dogmatic and see being in society is betraying the part of me that loves to be outside of it. And I'm learning how to hold both of those perspectives. There's value in both the youthful spirit and the elders wisdom.

What's the healthy relationship between these two forces, and how can we, throughout our lives keep them in conversation with each other? We need them both.

We need time in society. And we need time for solitude. We need time in the non-human world, in the land not entirely shaped by human hands, what we might call wilderness. We just have to remember that we belong there to. Chris's story should remind us to live life on our own terms. As he wrote in that letter to a friend, quote, to make a radical change in your lifestyle and begin to boldly do things which you may have previously never have thought of them.

That, I believe, is the legacy he left behind to escape the constraints of society as best we can, but also to learn from his lesson and always remember the importance of community.

Thanks for listening. It's up to each of us to navigate our own path between society and wilderness. Community in solitude. Until next time, I hope you'll consider what that right balance is for you. What constraints are worth escaping? Where can you find solitude? Where can you find community? How can you live life on your own terms? And if you're looking for community, I know one place to look.

The human nature Odyssey Patreon. There you'll find folks asking the same big questions and sharing their own answers. You can send me a direct message or leave a comment and join the conversation. As part of the Human Nature Odyssey Patreon, you'll have access to bonus episodes, transcripts of episodes, and audiobook readings. Your support makes this podcast possible. Thank you to Jesse, Alexis, and Michael for your feedback and notes on this episode.

And as always. Our theme music is Celestial Soda Pop. By Ray Lynch. You can find the link in our show notes. Talk with you soon.