Within an hour of Trump’s imposition of new tariffs, analysts at J.P. Morgan put out this guidance for their investors:

“We view the full implementation of these policies as a substantial macro economic shock not currently incorporated in our forecasts. .. these policies, if sustained, would likely push the US and global economy into recession this year.”

It’s not clear, of course, why the tariffs were “not currently incorporated in our forecasts,” given that Trump has been talking nonstop about them for a year, but hey—nothing about what the White House is doing makes any real sense, so whatever. And of course there’s every chance Trump will decide to do away with them tomorrow, or (more likely) bargain with one country after another, exempting those that decide to build Trump resorts.

But the impetuous imposition of steps that even Murdoch’s Wall Street Journal calls nonsense are only a short-term way to wreck the economy. To make sure it tanks forever, you need to work harder. Which, sadly, the Trump administration is doing,

Mark Gongloff and Elaine He at Bloomberg produced a remarkable timeline the other day showing in enormous detail how the Trump administration had, in a matter of weeks, undone twenty years worth of efforts to do something about the climate crisis. It’s not like the U.S. had been providing sterling leadership, but “nothing could have prepared us for the breadth or intensity of the assault on climate action that Trump has unleashed during his first months back in office.”

Every agency with any connection to the climate (meaning basically all of them) has been involved, from the Environmental Protection Agency to the Defense Department. International cooperation by NASA scientists, UN diplomats and more has been forbidden, and Trump appointees are meddling in state and local efforts to manage their own environments. Elon Musk’s crew, intent on dismantling the apparatus of government, has frozen research and funding and put vital expertise on the street.

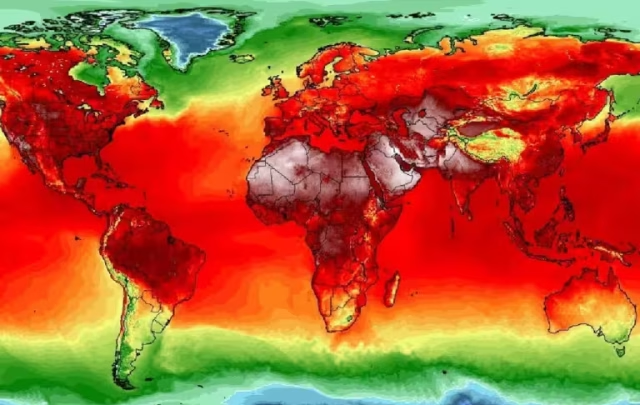

As a result of this all-out effort to destroy climate action here and abroad, the analysts at the big banks declared last week that the effort to hold temperature increases to two degrees Celsius—never mind the 1.5 degree target we set at Paris—are probably dead.

“We now expect a 3°C world,” Morgan Stanley analysts wrote earlier this month, citing “recent setbacks to global decarbonization efforts.”

To reiterate—this is not a statement about physics, which hasn’t changed in the last three months. It’s a statement about politics. And to be entirely clear, the big banks have done nothing to change that politics in any way—indeed, as they’ve all withdrawn from the Net Zero Banking Alliance in recent months, they’ve done their best to abet Trump’s efforts. And they don’t care now—As Politico pointed out, they’re eagerly figuring out ways to make money off the end of the world.

Morgan Stanley’s climate forecast was tucked into a mundane research report on the future of air conditioning stocks, which it provided to clients on March 17. A 3 degree warming scenario, the analysts determined, could more than double the growth rate of the $235 billion cooling market every year, from 3 percent to 7 percent until 2030.

That is to say, confronted with the probability of hell they’re figuring out a way to sell air conditioners to the devil.

But let’s be very clear about what a three degree Celsius rise in temperature will mean to the world’s economies. Happily, we have a brand new study from a team at the University of New South Wales in Australia to help us:

We found if the Earth warms by more than 3°C by the end of the century, the estimated harm to the global economy jumped from an average of 11 percent (under previous modelling assumptions) to 40 percent (under our modelling assumptions). This level of damage could devastate livelihoods in large parts of the world.

As lead author Timothy Neal explained,

To date, projections of how climate change will affect global gross domestic product (GDP) have broadly suggested mild to moderate harm. This in part has led to a lack of urgency in national efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

However, these models often contain a fundamental flaw – they assume a national economy is affected only by weather in that country. Any impacts from weather events elsewhere, such as how flooding in one country affects the food supply to another, are not incorporated into the models.

Our new research sought to fix this. After including the global repercussions of extreme weather into our models, the predicted harm to global GDP became far worse than previously thought – affecting the lives of people in every country on Earth.

The old models assumed that weather shocks in one area in any given year would be balanced out by normal life elsewhere, and hence the economy would adjust.

The modelling is usually based on the effects of weather shocks in the past. However, these shocks have typically been confined to a local or regional scale, and balanced out by conditions elsewhere.

For example, in the past, South America might have been in drought, but other parts of the world were getting good rainfall. So, South America could rely on imports of agricultural products from other countries to fill domestic shortfalls and prevent spikes in food prices.

But future climate change will increase the risk of weather shocks occurring simultaneously across countries and more persistently over time. This will disrupt the networks producing and delivering goods, compromise trade and limit the extent to which countries can help each other.

Which is to say that, even if clearer heads prevail and we decide to renounce our insane tariffs and the global economy resumes its current course, it won’t be able to compensate for the heat we are unleashing. The strain is already showing. Here’s another J.P. Morgan analysis from last week, this one on the insurance market

Insurance is now a crucial component of various financial transactions, often required for securing financing such as mortgages or auto loans and serving as an optional safeguard for purchases like travel, pets and appliances. Although insurance is often considered a long-term fixed cost in financial discussions, recent increases in property and casualty (P&C) premiums may affect consumer behavior. However, there can be a timing mismatch between insurance coverage and the long-term financing it protects, revealing a hidden future variable cost.

In this dynamic environment, homeowners insurance, a subset of P&C insurance, demands attention. With comprehensive coverage across the U.S., insurance data offers invaluable insights into the evolving landscape of physical risk in a major market. The total value of mortgage debt outstanding in the U.S. is a staggering US$20.7 trillion in 2024…

Currently, a confluence of inflation, climate change and disparate state regulations is both driving up insurance premiums and prompting private insurers to exit certain markets to maintain profitability.

Look, the financial future on our current course is painfully clear. Risks of bad stuff happening keep increasing, and our ability to hedge that risk keeps decreasing. Economies tank, and people suffer in extraordinary ways. The men and women currently in charge of our national fate can’t or won’t see that; Director of National “Intelligence” Tulsi Gabbard testified before Congress last week on why she had removed any mention of climate change from the country’s annual National Threat Assessment. Challenged on the issue by Maine Senator Angus King, she said

“I can’t speak to the decisions made previously, but this annual threat assessment has been focused very directly on the threats that we deem most critical to the United States and our national security,” she said. “Obviously, we’re aware of occurrences within the environment and how they may impact operations, but we’re focused on the direct threats to Americans’ safety, well-being, and security.”

The only good news I can give you is that this is not yet a fait accompli, and we have the tools we need to slow down the rapid heating and give our civilizations a chance. Remarkable news came from Africa last week, where solar mini-grids are starting to roll out at scale, thanks to $30 billion in aid from the World Bank.

In January, the World Bank launched a program to get power to 300 million Africans by 2030, a project that could attract $85 billion or more of investment.

“We’re in the inflection point,” said Yariv Cohen, co-founder and chief executive officer of Ignite Power. The Abu Dhabi-based company is acquiring the African mini-grid business of French utility Engie SA, which provides power to Mwale. “We’ve never had $30 billion allocated for energy access in Africa. We never even had $1 billion.”

Called mini-grids, they generate electricity for small communities that aren’t on national supply networks — and the economics suggest their time may finally have come. Plunging solar panel prices, more business-friendly regulation by African governments and international funding are now spurring a rapid rollout from Nigeria to Madagascar.

We could be doing exactly the same thing here, of course, but instead we’re giving fossil fuel companies a direct email line to the EPA so they can request immediate exceptions to any environmental regulations. And as Emily Atkin reports this week, the Department of Energy has instead built a “secret hit list” of renewable energy targets they want to take down before they can get enough footing to undercut fossil fuels.

The “hit list” is a collection of clean energy projects already awarded billions of dollars in grants and loans under the Inflation Reduction Act, bipartisan infrastructure law, and annual appropriations. The DOE is now seeking to cancel these projects. The list will be submitted to the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) and the Office of Management and Budget, according to two people familiar with the plan.

Among many other proposed cuts, the “hit list” includes six long-duration energy storage projects that have already had $156 million in federal funding obligated under the bipartisan Infrastructure Law. The grants for those projects were awarded in 2023, and “seen as vital for turning variable wind and solar production into a reliable, round-the-clock power source,” Canary Media reported at the time.

The reason these grants were seen as so vital for wind and solar’s future is because they were commercial test-runs of newer technologies. They were intended to “convince private investors as well as utility regulatory commissions that these are trustworthy investments,” Canary Media reported. “If that succeeds, power companies will greenlight more of these projects in the near future.”

The Trump administration is desperate to snuff out what PV magazine yesterday called a “real but fragile” solar boom in this country. (And also wind—an “anti-wind activist” was hired last week as the general counsel for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration).

So if you headed off on April 5 for your local Hands Off rally, I hope you’ll be demanding hands off Social Security and hands off immigrants and hands off federal workers—but also, hands off the future. We’ve got a chance, but we have to move now.