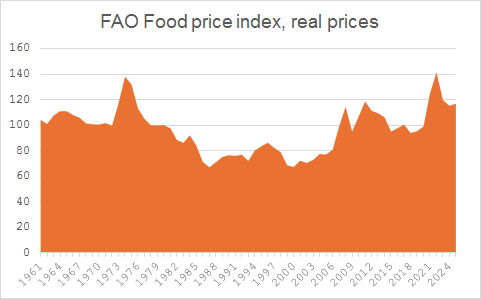

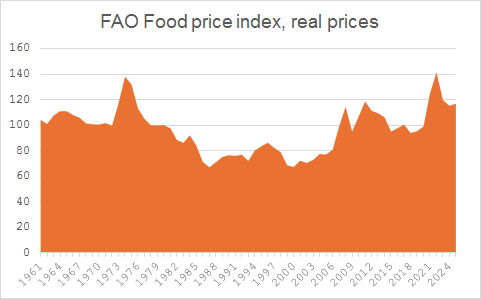

A global look gives a slightly different picture, with a less dramatic increase than in Europe or the USA. It should be noted that the long term (100 year) trend of food prices was falling until around year 2000, albeit with irregular hikes, mostly associated with oil prices. Carey W King writes in the Economic Superorganism that: “in the history of mankind, the cost of energy plus food has never been cheaper than around the year 2000.”

Notably, even if the FAO index is called a food price index it is a commodity index reflecting whole sale prices of a basket of important food commodities and not food products as they are bought and consumed.

Fossil energy, nitrogen fertilizers, food and labour

There are multiple reasons for why food prices are on the rise. There are major similarities between the FAO food price index and energy prices. This is also quite natural as energy is a major input in the whole food system. Transportation costs have increased a lot, which have two consequences. One is simply that costs increase, the other, equally important, is that competition decreases (which mostly leads to higher prices). More than free trade policies, the low cost of transportation has been the main engine for the economic globalization. On the farm input side, nitrogen fertilizers is very energy intensive. The trade in animal feed is huge and stretch over the oceans. On the farms, energy is used for machinery and in the later stages a lot of energy is used for processing, refrigeration etc. The increasing cost for nitrogen fertilizers will lead to both higher costs, but also lower yields as most farmers will reduce the use. This will in turn constrain supply and drive prices upwards. This will have a particularly high impact within the EU because of the combined impact of environmental and climate policies and tariffs (see below). The worsened global security situation has made many countries looking into supporting their own food production, which also comes at a cost compared to the prevailing-buy-cheap-in-world-markets paradigm.

The EU nitrogen trilemma. The EU has a number of policies having an impact on the use of nitrogen fertilizers. There are a number of environmental regulations such as the nitrate directive and the NEC directive (concerning air emissions). Then there is the carbon trading scheme which imposes rather high costs on EU-producers of fertilizers. From next year, also imports of fertilizers will be subject to the new “carbon tariff” (the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, CBAM), which means that imports essentially will be taxed in a similar way as the domestic production.

The EU stopped buying fossil gas via pipeline from Russia, but sanctions don’t apply to LNG from Russia. Perhaps there is some hidden logic here, but it appears to me as some kind of self-inflicted wound as LNG is considerably more expensive than piped gas. As a result of high fossil gas prices, EU fertilizer producers find it hard to compete, in particular with Russian producers that use gas that costs just a fraction of the price in the EU. It is actually so profitable that the Russian government has imposed a special export tax, which has supplied the government with a lot of funds. To cut a long story a bit shorter, the EU is now planning to impose special tariffs on Russian fertilizers.

Predictably, the farmers are protesting. Clearly, all these regulations on nitrogen fertilizers will impact food prices considerably. On the flip side, this will level the playing field for organic farmers and it will reduce nitrogen emissions!

The combined effect of higher energy costs and higher human energy (food) costs leads to higher labour costs. Even if the farm sector employ few people these days, the whole food chain has a lot of workers. An estimate by the FAO is that 1.23 billion people are employed in the agriculture and food chain and that almost half of the global population live in households linked agriculture and food chain livelihoods.

In the end you get, from an economic perspective, a vicious circle with high energy prices leading to high food prices leading to high labour costs leading to high distribution costs leading to supply chain disruptions leading to high food prices…

While this will be a great challenge for politics and for the poor, it might also be a start of a rebalancing the food system and the economy towards localized food systems with a higher share of self-sufficiency and ruralization of societies. But that is yet another story.

Climate change?

There is also the possibility that climate change starts to hurt food production. That is certainly a likely outcome in the future, but I am not yet convinced that this is already the case, at least not on a scale that influences global food production and food prices. Most qualified research on the topic discuss future risks and scenarios rather than today’s situation. But even a modest increase of freak weather event can have massive impacts on food prices. As the example of the EU shows, policies to combat climate change might have as high impact on food production as climate change itself. I don’t say that because I think it is wrong to make policies to combat climate change, but I believe it is essential to be clear that those policies, mostly, come with a price tag, which in the short term actually can be quite high as well as painful for those bearing the brunt of the policies, be it farmers or consumers.

* The oligopoly of retailers and food industries are very harmful for the quality of products and for the ability of small farmers and food industries to compete. Big retailers want to buy huge volumes of standardized products, something that a small scale diverse food system can’t (and should not) supply.