To start with two news snippets. First, more developments in the world of manufactured food, as detailed here and in following comments by the attentive Steve L. I aim to write an update on this topic later in the year covering what’s emerged since my 2023 book Saying NO to a Farm-Free Future – some interesting points of detail, but in general pretty much the story arc you’d expect from a technology over-hyped by journalists committed to easy techno-fixes rather than hard social change.

Second, the small farm future blog has just gone multilingual, with a Portuguese translation of this blog post of mine from back in 2015.

As it happens, both these snippets are somewhat relevant to the present post, which involves some thoughts on Andreas Malm and Wim Carton’s recent book Overshoot: How the World Surrendered to Climate Breakdown (Verso, 2024). And then I will probably be silent again for a couple of weeks while I do the final edits on my book.

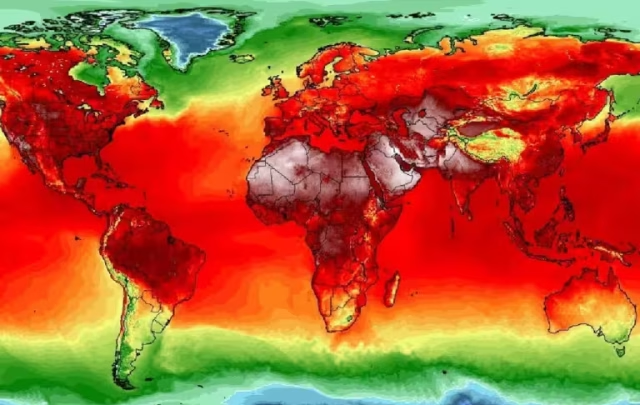

So, commenters here have been discussing the idea of ecological overshoot recently while I’ve been away. Thanks for that – another topic for a forthcoming post. But Malm and Carton mean something different by ‘overshoot’, namely the idea within international climate negotiation and analysis that it’s okay for global average temperatures to overshoot the 1.5oC or 2oC limits for global warming over preindustrial levels set by the 2015 Paris Agreement in the short term. The idea being that in the longer term, with greater wealth and technical know-how in the future, we’ll get this wild horse back under control.

The first half of Overshoot is a deep dive into the stupidity of this idea, and more specifically into the flaws of what Malm and Carton call the ‘bourgeois economics’ underlying it (I’ll come back to that phrase). I’m going to skip over that part of their book and just say that I found it convincing, and eye-opening. The ‘let’s pay later’ approach is a staple of contemporary economic thought that’s spectacularly inappropriate for dealing with climate change. Before reading Overshoot I had a rough general familiarity with the way that international climate negotiating worked and how unequal it is to the task before us, but the book brings home in impressive detail the full insanity of it all – a bit like a moribund medieval court obsessed with the minutiae of its obscure rituals and decorum, while the world outside the castle walls disintegrates.

Malm and Carton point up a tricky problem though. An awful lot of the capital circulating in the present global economy is tied directly or indirectly to fossil fuels, so if we ‘leave it in the ground’ or strand fossil assets, we basically tank the economy as we know it. Better than tanking the climate though, right? Yes, of course. But it does suggest that hand-wavy notions about a quick and economically smooth transition to low-carbon energy – no problem, nothing to see here, business as usual – are problematic in directly economic terms, quite apart from any technological or engineering issues.

Yet it’s around those technological and engineering issues, and their social correlates, where I found that Malm and Carton’s book started to get quite weird. In the lengthy Chapter 6, entitled ‘We are going to be driven by value’, they make a play for the idea that a quick transition to a fully renewable global energy system is readily possible. Nothing too unusual about that – many people embrace that notion. But the weakness and strangeness of some of the book’s arguments on this front made me wonder what was going on, especially because the authors are obviously otherwise smart and well-informed.

I’m not going to go too far into the renewables ‘transition’ issue, though I’ll be saying a little more about it in yet another forthcoming post. But Malm and Carton go to town on the idea that energy from the sun and the wind is free, and so can’t be turned into a profit stream, and so in turn is not selected over fossil energy in a profit-based capitalist system. At times, their argument waxes mystical: “Fossil fuels impose a zero-sum game on the land. The strange commodity exacts zones and corridors exclusively for itself. In the helio-aeolian flow, the land rather unfolds its leaves like a sunflower” (pp.179-80).

I’ve got no problem with mysticism as such. In fact, I think we could do with more of it. But not really in the sphere of energy economics. There are various non-mystical reasons why fossil fuels remain more profitable than renewables. Many of these are laid out in detail in Brett Christophers’ book The Price Is Wrong, which Malm and Carton refer to but don’t really engage with intellectually. These reasons encompass things like merit price and merchant risk in wholesale electricity markets, the difficulties of hedging renewable energy prices, the price of land, the price of electricity grids, the price of minerals, and the price of economic growth, the relative price of oil and gas as chemical feedstocks compared to power-to-X options, the economic rent associated with monopoly oil and gas supply, and a bunch of other things.

Not all these things are necessarily set in stone for all time in such a way that it’s inconceivable renewables will ever compete with fossil fuels. But you’d expect an in-depth academic treatment of climate and energy futures to engage with them properly, rather than unfurling strange arguments about free energy and sunflowers. When they do pick up on such issues, usually as brief asides or in footnotes, Malm and Carton tend to the airily dismissive, or to superficial talking points. An example is the bizarre argument that because renewable electricity is used as a source of power on drilling rigs, this somehow undermines the case for the fossil energy that’s extracted.

My point is not, of course, to justify fossil energy. It’s simply to dispute the notion we could easily transition from fossils to renewables if it wasn’t for those dang capitalists who insist on ‘being driven by value’.

So, what’s this strange turn in Malm and Carton’s argument about? It seems to me it’s about politics – more specifically, about some politics they don’t want to look at … and also some politics they look at a bit too much.

Reading a little between the lines, Malm and Carton basically divide contemporary political positions into four categories. First, ecomodernism – which, rightly I think, they view as a tall tale of nuclear power, radical decoupling of humanity from earth systems and overly technological solutionism. Second, left-wing politics and specifically Marxism, to which their colours are firmly nailed (non-Marxist forms of leftism don’t get much of a look-in in the book). Third, a suite of positions they variously call conservative, reactionary or business-as-usual, and which they’re none too keen on. Fourth and finally, what they call ‘anarcho-primitivism’. They say little about what this means to them – their lengthiest remarks coming, I think, on page 188 where they say “the two principal submissions from the anarcho-primitivist camp” are (1) that a transition from fossils to renewables would be ethically bad and (2) that it would be more desirable to have “generalised puritanism/privation or 7 billion people ‘or so’ removed from the planet”.

Trying to place myself within their scheme … well, I’m not an ecomodernist, and while I lean left on a lot of issues, I can’t really identify straightforwardly as a socialist, still less a Marxist. Likewise with conservative, reactionary or business-as-usual politics. So I guess I must be an anarcho-primitivist. I’m pretty sure that’s where Malm and Carton would pigeonhole my kind of thinking.

However, my kind of thinking isn’t really anarchist, or primitivist – not by their rubrics anyway. I don’t think using renewables instead of fossils is ethically bad, I don’t favour ‘generalised puritanism/privation’ and I certainly don’t want 7 billion people ‘or so’ to be removed from the planet.

It’s not my aim in this post to lay out in detail my own positions. In a nutshell, I’d say I draw principally from civic republicanism, agrarian populism and distributism, with a side of Luddism (albeit not the caricatured ‘anti-technology’ version) – neither left nor right in any simple sense, and not anarchist or primitivist either. But certainly a belief that we (by which I mostly mean we richer people in the richer countries) need to consume less stuff and less energy, to rethink what it means to live within limits (which, please, is not a ‘Malthusian’ position nor about privation and puritanism) and to rethink what it means to live as protagonists within a surrounding renewable ecology.

These are the kind of issues that I believe demand our attention. Instead ‘anarcho-primitivism’ basically serves Malm and Carton as a dismissive catchall category for any position that doesn’t embrace a high-energy status quo, justified by neo-Malthusian arguments about mass death in the absence of techno-fixes.

Just as Malm and Carton tend to lump everyone who doesn’t embrace high-energy techno-fixes into the anarcho-primitivist slot, so I must confess to having an increasingly hard time these days distinguishing between ecomodernism, most forms of leftism and most forms of ‘reactionary’ or business-as-usual thinking. All of these embrace a kind of sociological ‘things can only get better’ modernism which inevitably has to invoke heroic techno-salvation to keep it afloat.

Three points about this creeping ecomodernisation of mainstream politics by way of conclusion.

First, while techno-salvation narratives like to invoke groundbreaking new material technics, their political technics are shopworn. Government power, market forces … or, for Malm and Carton, a simple matter of “a bit of Marxism and common sense”. When they look for political thinkers to inform the present extraordinary moment in human history, Malm and Carton’s go-to choices are Lenin, Trotsky, Gramsci, Luxembourg and Adorno. I daresay there are some useful nuggets within the voluminous writings of that bunch to guide present thinking, but … well, no – the question of how revolutionary leftwing politics could seize the reins of a modernising, industrialising and energetically growing world that occupied those twentieth-century thinkers really isn’t the fundamental question today.

Hence my ‘overshoot, meet undershoot’ title – we’re seriously undershooting the level of political rethinking needed via an overshot faith in techno-salvation. Malm and Carton’s term ‘bourgeois economics’ to describe mainstream economic orthodoxy is revealing in this respect. Implicitly, this sees the problem as merely the dominance of economic thought by a particular class perspective that can be overcome by more accurate scientific analysis. That’s a really old kind of social science thinking that I don’t think is at all equal to present problems, and in fact is a part of them – the slippage from the idea of scientific truth to the idea of a scientific understanding of human society that generates the correct political prescriptions for it.

Second, where does the scorn for a caricatured ‘anarcho-primitivism’ come from? To some degree, I think it’s stitched deep into the fabric of our (eco)modernist historical culture, right across the political spectrum, as discussed often enough on this site over the years and as touched on in that ‘small farm romance’ article recently translated into Portuguese. Perhaps I’ll come back to it again sometime. A lot of people have a peculiar horror for the idea of a lower energy and more local world, necessarily involving more people working the land – whereas the idea of living in a suburb and working in an office tends to get a free pass. I think there will be more of the former and less of the latter in the future whether we like it or not, but it’s a bit odd that our culture is so resistant to the possibility that the former might have its plus points.

I’m not going to dwell on the reasons for that here, except to say that maybe one of them is the fact that so much of our public narrative about the future is in the hands of academics, journalists and politicos – basically wordsmiths, aka symbolic capitalists or the professional managerial class, who like to write and model on paper or on the computer, and for whom the idea of doing practical work instead typically evinces sheer horror. It wouldn’t hurt if a bit more of the public narrative was commanded by people who don’t write, analyse or model for a living.

Finally, Malm and Carton’s apparent inability to understand the difference between sunlight, which you don’t have to pay for, and electricity, which you do, is a bit ironic in view of strictures against ‘anarcho-primitivism’ as agrarian practice. The free availability of sunlight, and the costliness of electricity and other forms of energy, is basically why the future will most likely be more rural and agrarian, and why we will not be using electricity to split water to feed bacteria to make protein but instead will be using sunlight to feed plants to make protein, and other necessary nutrients. So the land will not be unfolding its leaves like a sunflower. It may, however, be producing sunflowers. And if it is, this will involve human work. That is, agrarian work. Local work. Practical work.