- The Samoan government announced June 3 that it has enacted a law establishing a marine spatial plan to sustainably manage 100% of its ocean by 2030.

- The country has also created nine new marine protected areas that cover 30% of its ocean.

- Fishing is prohibited in the new protected areas, which include a migration route for humpback whales.

- The plan became law on May 1.

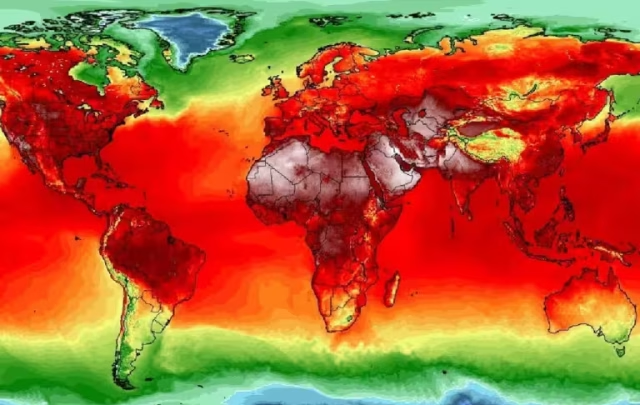

Samoa, an archipelagic country composed of nine islands in the South Pacific Ocean, is on the frontline of climate change. Rising sea levels, ocean warming and acidification all pose significant threats to the country’s coastal communities. To help protect its future, the Samoan government announced June 3 that it has enacted a law establishing a marine spatial plan to sustainably manage 100% of its ocean by 2030.

The plan, which became law May 1, also establishes nine new marine protected areas (MPAs) that cover 30% of Samoa’s ocean, an area of 35,936 square kilometers (13,875 square miles), roughly the size of Taiwan. The MPAs mean that Samoa meets its 30×30 ocean commitment, part of a worldwide agreement to protect 30% of Earth’s land and ocean by 2030 that countries made at the 2022 U.N. Biodiversity Conference.

Samoa’s ocean is filled with deep trenches, underwater seamounts and coral reefs teeming with sea life. The new MPAs protect a place that is home to critically endangered hawksbill sea turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata), spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris), blue sharks (Prionace glauca) and Taei’s dwarfgoby (Eviota taeiae), a fish found only on Samoan reefs. It is also a migration route for humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae).

“Samoa is a large ocean state, and our way of life is under increased threat from climate change, overfishing, habitat degradation, and much more,” Toeolesulusulu Cedric Pose Salesa Schuster, Samoa’s environment minister, said in a press release. “This Marine Spatial Plan [MSP] marks a historic step towards ensuring that our ocean remains prosperous and healthy to support all future generations of Samoans, who will rely on the ocean like us and as our ancestors did.”

The new law is the country’s latest effort to protect its ocean. In 2003, Samoa was one of the first countries to declare its ocean a sanctuary for sharks, turtles, whales and dolphins. In 2012, it created two coastal MPAs to help the reefs recover after a devastating 2009 tsunami. These were preceded by villagers launching their own local fishing reserves, which could make no-take zones to boost fish stocks. Samoa’s domestic fishing fleet has exclusive access to the first 24 nautical miles of sea around the islands, and there is a 50-nautical-mile buffer zone where fishing vessels longer than 15 meters (49 feet) are prohibited. The coastal MPAs, fishing reserves and fishing buffers are now part of the unified, power-packed MSP.

The nine new MPAs are the first Samoa has created beyond its reefs. They ban activities that could harm marine life or damage marine habitat; fishing, mining and drilling are outlawed. Coral reefs cannot be disturbed, so artificial reefs cannot be installed in these areas. Those fishing illegally could face fines of up to 1 million Samoan tala ($361,400) or imprisonment.

The largest new MPA is Toamoana, which features seamounts rich in biodiversity. It also includes Pasco Banks where, until May 1, fishers caught marlin (Makaira mazara) and yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares). The new Ala-l’amanu MPA lies on a migration route for humpback whales. Agavale MPA, Loto-i-toga MPA and Tumutumu MPA contain flourishing seamounts, and To’atugā MPA and Alataua MPA are fish breeding grounds. The Ae’a Savai’i MPA overlaps with a coral reef near the coast and the Usotu’ofe MPA runs on the border of American Samoa’s EEZ.

Before launching the MSP, the government held consultations in 52 political districts and raised awareness by means of radio advertising and a campaign bus. The planning process took three years.

Marian Gauna, acting oceans program coordinator for the IUCN in Oceania, told Mongabay that while Samoa’s MSP matches the 30×30 biodiversity targets set across the globe, it has one unique characteristic.

“A distinguishing feature of Samoa’s approach is its strong emphasis on local ownership and the integration of traditional knowledge, contrasting with the more centralized, top-down models adopted elsewhere,” Gauna said by email.

Samoa is not the first Pacific island country to put a marine spatial plan in place. Tonga also has a legislated MSP, and Palau has a bill in Congress. However, while the world’s nations committed to conserve 30% of the ocean, only 8.3% is currently protected and only 2.7% is effectively protected, according to the Marine Protection Atlas, a platform for tracking MPA developments.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the Pacific Ocean, marine protections are moving in the opposite direction. In mid-April, President Donald Trump opened the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument, a massive five-part marine protected area totalling 1.3 million km2 (490,000 mi2), to industrial fishing.

Enforcing Samoa’s new law will be key. Samoa currently uses satellites to monitor its EEZ, which is carried out by the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency, an intergovernmental agency with 17 member states. The Samoa Police Service also has a patrol boat, and on invitation the Royal New Zealand Navy patrols its waters.

Schuster, the environment minister, told Mongabay in an interview that policing the oceans will be expensive.

“It’s the most expensive component of implementing our MPAs,” he said. “Primarily what we want to work with is using satellite tracking, using drones.”

While he said he would like to add another patrol boat to the fleet, he’s clear-eyed about the task ahead.

“It’s not going to be easy,” he said.

“We don’t want paper parks. To ensure that we have effective monitoring, we had to come up with mechanisms to ensure that we are protected,” Schuster said.

One such mechanism in the MSP Samoa already uses on land: the polluter pays principle. Anyone who pollutes the environment must pay for the damage.

Isaako Papalii, a fisheries officer for the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries in Samoa, told Mongabay in an interview that he’ll patrol the markets and fine anyone selling endangered species up to 10,000 Samoan tala ($3,600) per unit of fish, and double that if he sees parrotfish for sale.

Papalii has seen the effects of climate change firsthand, as the fish have moved and changed habitats. However, he said the biggest challenge facing the ocean lies elsewhere.

“The biggest threat is people. We are not protecting [the ocean], we’re abusing. We take it for granted,” he said. “We never think about what the fish stock will look like in the next 10 years for our future.”

He expressed optimism the MSP will change that:

“Hopefully [the] MSP will educate more people, especially the community, on [the] economic importance of the ocean.”

Greg Hopping, owner of Troppo Fishing Adventures, a charter company in the capital city of Apia, told Mongabay in an interview that once the MSP is in place, enforcement will be essential.

“The issue is money. They can’t afford to put fuel in the boats. Even though they’ve got a patrol boat donated by Australia, they can’t afford to take it out and patrol some of those waters,” Hopping said.

The village of Poutasi on the island of Upolu shows how bonded Samoans are with the sea. Traditional fishing canoes rest outside nearly every home. After the 2009 tsunami devastated the village, Poutasi created its own community fishing reserve to protect its reef..

Poutasi village High Chief Tuatagaloa Joe Annandale told Mongabay people are acutely aware of climate change. Waves lap beneath the deck of the house he built two decades ago, and further land erosion may mean he needs to leave within the next five years.

Annandale said it should now be dry season, but the village is facing heavy rain and severe flooding that drives soil into the sea along with any chemicals used on land. He says he can see the change in front of his home.

“I used to have nice white sand; it’s now murky. If you don’t have healthy coral, you don’t have healthy fish,” Annandale said in an interview.

The loss of fishing grounds was one of the concerns Samoans raised during the consultation process, but Annandale said members of his community understand they need to adapt:

“They limit [the] way you can fish, but I think our community, we’re learning lessons the hard way. They now accept [the changes].”

This is because they have already seen results with their own community fishing reserve.

“The local fishermen [say] there’s more fish now. This is one of the good things about an MPA,” Annandale said. “Sure, you’re deprived from fishing in those particular areas, but it’s giving a chance to the fish life in those areas to breed and multiply.”

Marine biologist Schannel van Dijken has watched the sea eat away at the land around the coastal community where his family lives on the island of Upolu. He has seen his family create seawalls with rocks and broken coral from the nearby lagoon to help keep the ocean at bay.

“The water is coming close to our ancestral grave sites, which used to be far away from the water,” he told Mongabay.

Van Dijken, the senior director of marine heritage and Aotearoa country program lead for the U.S.-based NGO Conservation International, was on a team of researchers who surveyed Samoan reefs in 2022. Within the two existing coastal MPAs, they found healthy, heat-resilient corals that had survived the massive heating events Samoa has experienced in the last decade.

“Like humans [who] handle stress differently, so do corals. Heat tolerance comes from a mix of genetic factors, local adaptation and sometimes the type of symbiotic algae the coral has,” van Dijken said in an interview with Mongabay. “It’s important to note that while these heat-resistant corals can be found, their ability to keep up with the pace and intensity of climate change is still uncertain. But it gives us valuable tools for reef restoration.”

The team left temperature loggers on the reefs, which will stay in place for five years collecting data for further research.

“I think Samoa is like the quiet achiever in this space because it has legally adopted [the MSP] and I don’t think the other countries [that] have made declarations have actually got over that hurdle just yet,” van Dijken said.

Schuster said the Samoan government’s next goal is fundraising so it can implement the plan: 40 million Samoan tala ($14.5 million) over the next five years.