The importance of energy and other resources for the modern economy and the linkages between the real economy and the financial economy and money are at the core of my on-going research into biophysical economics, which hopefully will the shaped into a book in the coming year. Triggered by a couple of articles in the blogosphere, I offer these thoughts on some aspects of it. They serve the double purpose of me having to formulate myself which sharpens the mind and hopefully I can get much appreciated feed back from my readers.

”I predict that the world economy will shrink in the next 10 years. I think that this is bound to happen because of energy and debt limits the world economy is hitting,” writes Gail Tverberg in the Our Infinite World.

”It’s starting to look as though the global economy may have peaked in 2023.” writes Tim Morgan of the Surplus Energy Economics in the article, Has Growth Ended?. He also believes that the combination of rising energy costs and debt are the main reasons for this. In addition, he means that the GDP-calculations are flawed so that the economy is contracting already, even if GDP figures say otherwise.

There are other, more mainstream, indications of that the economy is losing steam. The US economy experienced a contraction in the first quarter of 2025, primarily due to trade. It will probably contract further due to the reckless politics of its president. The European economy contracted 1.9 % in 2024. The International Monetary Fund expects a slowdown in growth for advanced economies, with some countries potentially falling below 1% growth. Global GDP growth per capita seems to slow down and also become more volatile over the years. Of course, the global economy as well as national economies experience periods of growth, of stagnation and recession, that is inevitable and no big deal. It is very hard to know when a downturn is just a temporary event and when it signals a new trend or perhaps an indicator of a whole new phase.

Personally, I have no firm opinion other than that I know growth will end sooner or later and that growth is not what humanity needs.

There are many things to say about the GDP as a metric. Clearly the GDP is not a measure of well-being. It is also not a measure of wealth at it measures flows and not stocks. I will not repeat all the criticism of the GDP here, but focus on one important aspect. The GDP is, or is supposed to be be, a measure of economic activity, of throughput. But can we trust and rely on the GDP even within its narrow definition, i.e. are the figures of GDP growth reliable and do they reflect a bigger supply of goods and services?

The GDP is a measure within the economy and the link to actual goods or services is only the money spent on them. This means that if some item or service increases in price its contribution to the GDP increases, without us getting anything more. Or conversely, when stuff is cheaper they contribute less to the GDP. For public services (well not only “services” but all public expenditure), the contribution to the GDP is basically the cost for providing them. If you increase the number of teachers or raise their salary the contribution to the GDP will go up, if you increase military spending, the GDP will go up.

Services supposedly take up a very large share of the GDP in most advanced economies. But that is mainly due to two facts. First, a lot of work which earlier was done within primary and secondary industries is now made by contracted service providers, ranging from management consultants over legal advice, to cleaning and maintenance. Second, the “value” of a service in the GDP is the “value added” which basically means that expensive services such as medical services, real estate management and financial services contribute a lot to the GDP. For a normal US citizen the cost of medical services is exorbitant, but that is managed through equally expensive insurance. The net result is an inflated GDP. GDP grows but the prosperity of people doesn’t.

There are more complexities involved in measuring the GDP over time. As expressed (2019) by Erald Kolasi and Blair Fix in their very illuminating article, Why We Should Abandon Real GDP As A Measure of Economic Activity:

”Because ‘real’ GDP is based on an unstable unit (prices), its value is fundamentally ambiguous. Different methods of ‘correcting’ for inflation and quality changes, yield different values for the growth of ‘real’ GDP. ”

They show that depending in the base year chosen, the growth of the US economy over 70 years, varies with 30%. The official figure is the the highest possible value of those, probably not a coincidence. Tim Morgan claims that the GDP is not measuring the real economy and that it is distorted by debt. In his view material prosperity is already trending downwards on a global scale and has been falling for decades e.g. in Europe.

Energy

Tim Morgan emphasises the increasing cost of and energy needed for obtaining energy – Energy Cost of Energy (ECoE). In essence, if EcoE rise, ”producers’ costs increase, whilst the prosperity of the consumer of energy is reduced”. From less than 1% in the quarter-century after 1945, ECoE of all forms of energy have risen relentlessly, from 2.0% in 1980, and 4.2% in 2000, to 11.0% now, according to his calculations.

The Energy Cost of Energy concept is based on much the same as the better known (?) Energy Return on Energy Invested (ERoEI) or Energy Return on Investment (EROI), even though it is expressed differently, as a percentage instead of a ratio. According to Tim Morgan, the advanced and complex economies need a ECoE below 5% to thrive while the simpler emerging economies can operate with a 10% ECoE. The proponents of the existence of a critical ERoEI limit for modern civilization, will often quote a figure in the range of five, i.e. that 20% of the energy is used to obtain energy. Note that there are many ways to calculate the ERoEI (and ECoE) and that there is a huge difference between ERoEI at well-point and at point of consumption, or even for a whole lifecycle, where you would also include waste management and recycling (even such as CCS for the burning of fossil fuels). You can read more about that in the article Energy Return on Investment: A Unifying Principle for Socio-Ecological Sustainability by Rigo Melbar and Charles Hall, the main developer of the EROI concept.

While I do think the ECoE and ERo(E)I concepts have considerable merits, I fail to see that they would have such absolute and dramatic effects as some claim, for a number of reasons. All forms of energy are not equal, most apparently one can’t compare food energy with external energy sources. When traditional farmers use swiddening as a method for clearing land, their use of energy is enormous and most of the energy is just wasted, the ERoEI is certainly less than even 0.1, i.e. the energy embedded in the wood burned would be more than ten times the energy in the food obtained. For human energy vs food energy, the return is very high though, which is the reason for why swiddening has been the preferred method in places with low population densities. This is, perhaps, an extreme example and one can conclude that this kind of energy wastage is not possible when population intensity goes up. We would certainly run out of forests (=Energy) rapidly if we tried to feed the world by swiddening today.

But even in a situation more applicable today, it seems to me that ECoE or ERoEI is not determining if a complex society is possible or not. I know that there are hidden ”fossil subsidies” in solar panels, but let’s imagine a situation where the whole process of producing, transporting and mounting solar panels and all the associated infrastructure (batteries or other ways to store energy) operate with solar electricity as the main or only power, and that the costs for this system is reasonable. It really doesn’t matter if you use 15% or even 50% of the energy produced by solar power to keep the system going as long as energy is cheap enough. You just erect more solar panels to get the energy needed. In a similar vein, the fact that solar panels just convert some 20 percent of the solar energy to electricity doesn’t matter as long as they are cheap enough. There are models that have a much higher efficiency, but they are too expensive for commercial use.

I still have my doubts about if a ”modern complex and high-tech society” could run exclusively on solar and wind, because of resource constraints, complexity and intermittency. But let us not go further there at this stage; my example still constitutes a relevant objection to the notion that you need a certain ERoEI or ECoE to manage a modern civilisation, unless you come down to situations where you need almost all energy or even more energy to produce one unit of energy (something that sometimes seems to be the case with new promising technologies which are supposed to save us).

Gail Tverberg has another take on energy, even if there are similarities with Tim Morgan’s. In her analysis, the actual cost of energy is very important. The critical point is that the cost of producing energy can’t be too high because consumers (i.e. both end consumers and manufacturers and intermediaries) can’t afford it. Meanwhile, the producers can’t afford when prices go too low. This is a driving force behind the volatility of oil prices the last twenty years. A prime example of this is the US shale oil and gas production, which is not profitable when prices fall towards $60 per barrel. Canadian tar sand oil is even more expensive to extract (oilandgasinfo.ca).

I find her approach sensible and one can observe the workings in real life. Still, I assume that in the longer term, we could manage an economy based on 100 dollars per barrel, or even higher, as producers and consumers would adapt. It would be a bit different, but I fail to see that it would be a total game changer. Gasoline cost $0,9 per litre in the US, $1.6 in Sweden, $0.5 in Qatar, $1 in China and $3.4 in Hong Kong. All of these economies are working. (It might be an interesting thing to explore if the different positions in the global value chains can support varying costs of energy, in the same way as the position in the global value chain seems to determine wages, stringency in environmental regulations etc.). Even with 100 or 200 dollars per barrel, oil provides very cheap energy compared with human labour. I haven’t looked into how the cost of fossil fuels as a feedstock for industry (fertilizers, plastics, chemical) impacts the economy, that might actually be very important, as some 13% of the oil is used for other than energy purposes.

Energy is important, very important. And clearly the net energy supplied to the economy goes a long way to explain growth. But the causality is perhaps not only one way. It might also be the case that we consume more energy when we get wealthier. Driving cars or flying for holidays, air con and streaming of films, come to mind as uses of energy which is rather a result of a growing economy than the other way round.

Does energy create growth or do we consume more energy when the economy grows?

Debt

Both Gail Tverberg and Tim Morgan make a case for that debt levels are unsustainable. I don’t feel hundred percent convinced about those claims. I am sure that the debt of some people, companies and countries are untenable in the long run. And clearly if that somebody is important enough (the US government comes to mind) and goes bankrupt there could be huge shock waves in the hyper-connected global economy.

But the linkage between the debt, financial asset inflation and the ”real economy” seems blurred to me. Financial capital, whether in the shape of paper money, digital currency, bonds, derivatives or real estate, can be seen as a claim on the economy. At any point of time you can sell the asset and use it to employ people, or buy goods and services. Without that link, assets are simply imaginary. And perhaps they are, because it is equally apparent that the billionaires can’t sell all their assets and make these claims as 1) there would be no buyers and 2) the prices of everything they want to buy would sky-rocket as a result of the increasing demand.

Even if a company, a person and a government can borrow money to finance investment or consumption, the debt doesn’t really create that possibility for investment or consumption on a system level – it is the availability of labour, real capital (machinery, buildings etc.) and natural resources that determine the size of the economy. Increasing debt doesn’t create a bigger labour force or more iron. In the same way, a reduction in debt and wealth doesn’t necessarily mean a corresponding contraction of the economy. For instance, the global financial crisis 2008 incurred losses in household wealth of about $11 trillion in the United States; $8.5 trillion in financial assets and $2.5 trillion in housing assets (IMF). Meanwhile the GDP contracted, but more in the range of $0.3 trillion between 2008 and 2009.

Chicago Board of Trade 2012, photo: Gunnar Rundgren

Debt may still impact growth by allocating resources to some things, persons or sectors rather than another. The balance between consumption and investment, for instance, has a impact on the economy. On the other hand, again on a system level, the impact may be smaller than most believe, because what is spent on consumption may very well be translated into more investments by the companies supplying the goods or services that are consumed. Again, there is a question of causality. Does debt create growth or does growth create debt? A lot of debt is based on the assumption of growth. That is clearly the case of the US government. Currently, on a global level public debt is expanding more rapidly than the GDP, while private debt is shrinking.

Does debt create growth or does growth create debt?

Money

Some see the present monetary system (in particular money creation by banks) as the central component or driver of an untenable economic system. For sure, monetary policies are important, but I fail to see how money creation can create growth; my objections are basically the same as with debt as money can be considered a version of debt. If money creation really could create growth, some governments, considering their obsession with growth, most certainly would have figured out how by now.

There are still some very interesting things to discuss about money. Human ecologist Alf Hornborg says that we can trace ”much of our ecological, social, cultural, and existential predicament to the fetishised artefact of general-purpose money”, in his new book Liquidate: How Money is Dissolving the World. I find his analysis (which has been articulated in several articles earlier) interesting, but I am also not sure about the causality here. I just started reading the book and I will most likely come back with some more reflections or a review later on.

Information, communication, transactions and complexity

I wrote in my recent article about complexity, that there is an energy cost to complexity. There are also huge information, communication and transaction costs for complexity. That modern society, including the economy, governments, etc. is a very complex system can hardly be disputed, and it is equally apparent that such a system needs a lot of information and exchange (transactions) in order to work properly; after all that is more or less the definition of complexity.

I am quite convinced that there is a lot of complexity slack in organizations, such as expressed in Parkinson’s law (the number of workers within public administration or bureaucracy tends to grow, regardless of the amount of work to be done.). As a farmer and for a long time engaged in the standards and certification systems of the organic sector, I can certainly see how complexity has inherent growth mechanisms and that this complexity is stifling innovation and development. Having said that, I also think it is obvious that the modern civilization needs high levels of complexity in order to work. And complexity needs huge flows of information to work.

Digitalization and AI is basically about information processing and management and they require huge energy inputs. Digital work is even more dependent on energy than many other kinds of work. In my analysis, AI is not primarily a technology that will give us unprecedented possibilities, but primarily a technology that is absolutely necessary for managing the ever increasing flow of information and complexities in our society, in the same way as digitalization has been for around fifty years. (Despite all this, there is little evidence that these new technologies actually increase productivity in the economy at large, but that is again another story).

Complexity has strong links to energy which means that the combination of increasing energy costs and increasing complexity is a potential game changer. Even more so if the energy system also requires high levels of complexity such as nuclear power or a electric grid run on renewables.

——

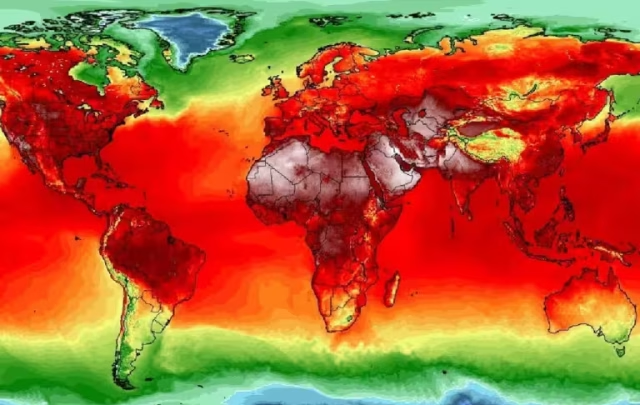

There are other factors which also are very relevant in the context of limits to growth and my book project, such as population, resource use, climate change and loss of bio-diversity. By and large I think all these aspects are part of the same story.